Thus would an apt summative headline on the most recent study of the Pew Internet & American Life Project on the possible future of gamification read, which was released on May 18, 2012.

But that would also be a non-story, of course.

The report is a breakout from the 2012 edition of the bi-annual “Imagining the Internet” survey conducted by Pew Internet and Elon University. The survey invited roughly a thousand hand-selected and self-recruited Internet experts to assess eight “tension pairs” – two diverging scenarios on the state of the Internet in 2020 with regard to one topic –, select the one they more agreed with, and explain their choices in writing.

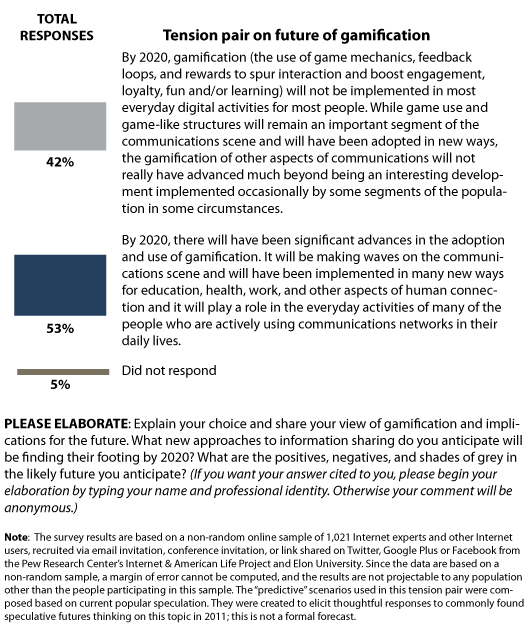

The result of the “gamification” tension pair: 42% chose “By 2020, gamification … will not be implemented in most everyday digital activities for most people”, 53% chose “there will have been significant advances in the adoption and use of gamification”, and 5% did not responded. The rest of the report highlights excerpts from the written responses, covering various topics and positions.

I was playing in my head how pundits and press might spin this non-story into a story (“Majority of experts agree on bright future for gamification, new study finds”), but my trusty google alert showed me that the media were already quicker: “Gamification taking over our lives, study finds”, “According to a new study, gaming is going to be creeping into our lives in a big way in the years to come,” etc. Sigh.

Bickering aside, the Pew report is indeed an interesting and rich data point. If there is any overall “message” to take from it, I’d say it’s the very undecidedness of its result and the diversity and tentative quality of the statements it collects. Put differently, “the jury is still out.”

Apart from that, the main value I found in reading through the highlighted statements in the report (and the full statements collected here and here) is getting an insight into the discourses, frames and conceptual models that Internet users and thinkers are using to make sense of “gamification.” Along those lines, some observations that stood out for me were:

Little gaming expertise

As an artifact of the study design, which attempts to cover broad general Internet trends, the collected expert voices come by-and-large from Internet theory, sociology, and anthropology – danah boyd, Clay Shirky, Amber Case, Paul Jones, Jeff Jarvis, David Weinberger, Stowe Boyd, Steve Jones, to name but a few. All names beyond reproach, for sure, but also all people with little explicit expertise in game studies, game design, or the gaming industry. This is not a bad thing per se – it’s a refreshing outside view –, but it should be kept in mind when reading the statements.

Confused terms

Partially as a consequence of such lacking domain expertise, the statements showcase a frequent confusion of gamification, serious games, games in general, and even virtual worlds. Although the study took care to define its understanding of gamification – “the use of game mechanics, feedback loops, and rewards to spur interaction and boost engagement, loyalty, fun and/or learning” – people’s understandings were all over the board, as the report itself notes:

“Survey respondents framed their conception of “gamification” in highly varied ways, ranging—in game-name terms—from massively multiplayer online games such as Star Wars: The Old Republic to World of Warcraft (a “virtual world”) to Farmville (social network-based game) to Angry Birds (popular smartphone app) to Foldit, a game that researchers used to crowdsource a scientific solution to an AIDS question, to training simulations, to the “points” (sometimes only in terms of social currency) one gathers for action in social interactions online, including having the most Twitter or Facebook connections or mentions.”

This is crucial to frame the survey result: When people were speaking for or against a presumed future pervasiveness of gamification, they were more often than not actually thinking of (serious) gaming in general. It is also misfortunate in that it implicitly supports the efforts of some gamification pundits to establish the term “gamification” as a catch-all for anything remotely game-related.

Playbour and the political economy of gamification

I really, really like the fact that PJ Rey and others framed gamification in terms of the more general critical analysis of the political economy of the Internet, especially “free labor” (Terranova), “playbour” (Kücklich), and “weisure” (Conley), and that the authors of the report highlighted this as one main observation. In her review of Jane McGonigal’s book Reality is Broken, Heather Chaplin has made some moves in this direction, as did Trebor Scholz in another context, but we do need more solid criticism of gamification and the web in general in their often exploitive economic relations covered up by an ideology of “fun,” “play” and “self-expression.”

My favorite quote in this regard comes from Brian Harvey:

“This (gamification, SD) is a matter for intervention, not prediction. It should be illegal, with serious penalties (life in prison, for example), to use information ostensibly gathered for one purpose for something else without an explicit, competent, well-informed opt-in by the person who legitimately owns the information—not third parties, such as pharmacies or search engines or ISPs. Someone who puts up a game-like thing in order to coax people into providing free labor, or in order to collect information for any commercial purpose, is committing a profound violation of human rights.”

“Generation G” and the “Grandma loves romance novels” fallacy

Two assumptions running through many statements are “games = young people” and “young people like games = young people like and demand gamification”. To quote: “‘We have an ever-increasing number of individuals (mostly younger than 35 years old) who have grown up with videogames and have been conditioned to pursue online rewards,’ said Marcia Richards Suelzer, senior writer and analyst at Wolters Kluwer, echoing the sentiments of many survey participants.”

Demographics aside – according to the most recent figures of the Entertainment Software Association, the average age of the US gaming population is 37 years –, this reiterates the problematic “Generation G” or “gamer generation” trope. The idea is that growing up with video games was a formative experience for a whole generation of people that powerfully shapes their preferences and expectations towards workplaces and life in general. To my knowledge, this trope was given birth to by authors John C. Beck and Mitchell Wade in their 2004 Harvard Business Press book Got Game: How the Gamer Generation is Changing the Workplace. They drew their conclusions from one survey among US business professionals with often poorly constructed, leading questions, do not report on the statistical (un)significance of their results, consistently jump from correlation to causation, and consistently over-interpret results.

There is no doubt that playing video games has been and continues to be a crucial part of the life experience of millions of people across the globe. It is very likely that this will have some effect on them individually as well as culture as a whole. But to the best of my knowledge, nobody has yet conducted a solid empirical study to explore what these effects might be. So to me, the “gamer generation” sits right next to “digital natives” in a spectrum between unexplored myth and gross overgeneralization.

Furthermore, the notion that “because young people like games, they will like and demand XYZ to be gamified” showcases what I like to call the “Grandma loves romance novels” fallacy – a fallacy that also appears from time to time in the discourse on serious games: “Kids like games but don’t like school books. So let’s replace math books with maths games, and kids will love maths.” The silliness of this non-sequitur becomes fully apparent when we replace kids and games with grandmothers and romance novels: “Grandmothers love romance novels but don’t like school books. So let’s replace maths books with romance novels involving maths, and grandmothers with love maths.” The medium in and of itself does not mean that whatever is conveyed in that medium automagically gains relevance, meaning, and value to a person preferring that medium.

This silliness is even more pronounced when we move from “games” to “gamification”: “Grandmothers will like and demand romantic novelization. Soon, no grandmother is going to visit a dentist who doesn’t dress up like Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy and deliver his diagnosis in florid Jane Austen-style.” Just because you enjoy one thing in one context doesn’t mean you would want superficial properties of that thing indiscriminately slathered onto every other part of your existence.

Competition

Several quotes seem to indicate that games (and/or gamification) are always competitive: “The word ‘gamification’ has emerged in recent years as a way to describe interactive online design that plays on people’s competitive instincts”, “It is not wise to make everything into a competition”, “Gamification has little use in cooperation”, etc.

Now it is true that most standard definitions of games include an element of conflict or strife. To quote but two definitions currently commonly referred to in game studies: “A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome.” (Katie Salen & Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play, 2003, p. 96). “A game is a rule-based formal system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are optional and negotiable.” (Jesper Juul, The Game, the Player, the World, 2003)

But both in Salen’s and Zimmermann’s “artifical conflict” and Juul’s “effort,” nothing demands that they derive form the competing force of another player. The wealth of single player games and cooperative games (from Pandemic to FarmVille) betrays the assumption that games are always necessarily competitive. This is not to deny that direct or indirect competition or comparison fuel a large chunk of gameplay. I only wish to emphasize, counter to the assertion made by Stowe Boyd in the report, that there is a big role for game design to facilitate collaborative and cooperative processes.

Neuromania

Both respondents and the report allude to the neurosciences as an empirical basis for the effectiveness of gamification. To quote the second paragraph of the report:

“While some people dismiss gamification as a fad, neuroscientists are discovering more and more about the ways in which humans react to such interactive design elements. They say such elements can cause feel-good chemical reactions, alter human responses to stimuli—increasing reaction times, for instance—and in certain situations can improve learning, participation, and motivation.”

Despite a critical evaluation of this trend, sociologist Simon Gottschalk echoes the same framing in his statement: “The findings yielded by the emerging field of neuroscience provide powerful tools to understand and hence manipulate the human brain … In light of advances in neuromarketing, there is no reason to believe that the most powerful economic entities are not going to use that knowledge (rewards, feedback loops) to spur interaction, boost loyalty (especially brand loyalty), and provide neural pleasures when consumers and customers do what they’re told.”

While it is to be forgiven that an online survey response doesn’t reference sources, I find it problematic that the authors of the report themselves allude to “neuroscientists” without providing sources to back up their portrait. It is problematic because they are implicitly reinforcing a rhetorical maneuver made not only by certain gamification pundits: appealing to neuroscientific studies as a presumed new highest authority when it comes to ‘the truth’ regarding the human condition. Beyond that, to my knowledge – and please, dear reader, correct me in the comments if I’m wrong –, there have been no neuroscientific studies conducted yet on the effectiveness of gamified applications.

Play versus work

The relation of play and work is a big issue that continues to befuddle the academic study of play and games, because it connects directly to an even more fundamental question, namely, in what way games and play are “separate” from the rest of everyday life. (Some of the best recent analysis on this I found in Bonnie Nardi’s excellent anthropology of World of Warcraft.) Terms like “playbour” and “weisure” quoted above already indicate how in society at large and digital (game) culture in specific, the presumed boundary/opposition of play and leisure on the one hand and work on the other have become more and more blurred. Modding, e-sports, or goldfarming are further cases in point for play activities that have become professionalized, instrumental, even waged activity.

In light of this, it is more than anything interesting to see that outside game studies, folk theoretical notions of a play/work dichotomy still prevail, and how these notions look like. As a highlighted quote states: “Playing beats working. So, if the enjoyment and challenge of playing can be embedded in learning, work, and commerce then gamification will take off.”

I think we are still at the very beginning of understanding the fundamental role of play (as a mode of experience and conduct) in contrast to games (as designed artifacts) in supporting the emotional, motivational, and social affordances of gameplay. And I am actually confident that studying “gamification” will help to surface and contour its contribution. So I would just want make two short remarks on what I find missing in this folk theoretical play/work opposition: First, as Csikszentmihalyi already documented in his study of flow-inducing activities in the 1970s onwards, people regularly find the most flow, meaning, fun etc. in their work already. Second, to the extent that gameplay and work are different, “game elements” and “feedback loops” are the least important bit of that difference. As I find time and time again in the interviews I’m currently conducting for my PhD, it is autonomy, voluntariness (or the lack thereof) that makes or breaks the playfulness of a situation.

Some reflection recommended

Overall, the Pew report offers a rich variety of often contradicting voices raising a large number of issues, resulting in a multitude that is hard to reduce to one overarching “sentiment.” That alone makes it a welcome counterpart to the confident and unilaterally optimistic predictions of technology consultancies like Gartner or Deloitte also quoted in the report. The only thing I really missed was some critical reflection on the part of the authors about the discursive effects of the report itself. When an esteemed scientific body like the Pew Research Center puts out a report on “gamification,” and a report titled “Gamification: Experts expect ‘game layers’ to expand in the future, with positive and negative results”, that already legitimizes the topic in a major way. But that is indeed a minor quibble.

Hi, as someone new trying to assess the impact of gamification on social and economic behaviours, and understand what it is, and isn’t, I really appreciate your analysis of the Pew study, and the links you provide to other sources. I think the ambivalence of the findings illustrates that too much is being said about something about which too little is known!! Thank you.

While I agree with pretty much all of what is in your article, I think you do your argument a disservice

using the substitution game (romance and grandmothers). You have substituted a

medium (“games”) with a medium and content combination (novels + romance). If

you stayed with just a medium (“novels”) then it the substitution doesn’t

descend to the farcical. This is further mitigated if you stop taking things to

the extreme (ie “will love”). How about this;

“Kids enjoy games but don’t enjoy

school books. So let’s replace math books with maths games, and kids will enjoy

maths more”. I’ve seen this with the difference between my son sitting

down to a list of 10 math’s questions that I have written out for him to do vs

his eagerness to get on to mathletics and race the computer to answer a similar

ten questions.

Using the grandmother substitution; “Grandmothers

enjoy novels but don’t enjoy school books. So let’s replace maths books with novels

involving maths, and grandmothers with enjoy maths more”. I think that is

quite possible and for a real life example, I suggest you read “Reaching for

Infinity” which is a novel including maths (and coincidentally romance) which I think does

make maths seem a lot more interesting and would probably pique most people’s

interest in some of the things mentioned.

Regardless even of all of this, I don’t

know why detractors of gamification (and yes I dislike the term too but it

seems we are stuck with it) always go with the extreme negative such as “indiscriminately slathered”.

I dare say there aren’t many things that if

really badly implemented or “indiscriminately slathered” will actually add

benefit. So lets stay with the common sense position which is that if relevant aspects

of game design are implemented into a non game situation in a thoughtful way

then they will probably help. If not, then they will probably be wasted or even

a hinderance. It might lead to a

better discourse of how to do this

well rather than the untrue and unhelpful posturing of either extreme; “gamification”

won’t always be useful and it won’t always be a waste of time.

Just sayin….

Hi Patrick,

thanks for your thoughtful reply. I perfectly agree with the common-sense-position as outlined by you that thoughtful implementations “will probably help” and thoughtless ones probably won’t. I also know a couple of well-designed serious games – e.g. “Play Ludwig” on elementary physics – that do get their players excited, so I agree with your point that a proper, thoughtful implementation of a specific learning content in a medium that is closer to the preferences of a specific audience might make the topic more appealing to said audience.

The position I am taking issue with is the assumption that audience A will *automatically* enjoy and seek out content on topic B once it is served in medium X. That’s helpful, but not *sufficient*. My preference for a medium does not automatically translate into my interest for a topic. That’s the fallacy I’m concerned with: Medium != relevance.

True – all else being equal, if forced to learn about topic B, and given the choice whether to study it in your prefered medium X or some other medium Y, you will likely prefer medium X. But this does not translate into you *actively seeking out* material on topic B, just because it appears in medium X. The existence of maths games does not mean that school kids will automatically voluntarily pick up maths games, rather than the plethora of commercial games available. There still needs to be something that makes *the topic* mathematics *relevant to them*, that connects it to their needs, cares, goals, interests. Creating this connection is a big part of what good learning design (in any medium) is about.

Only well-designed serious games or gameful applications will be engaging – true. It’s not enough to “just make it a game/gameful.” Contrarily, making it a *well-designed* game/gameful application probably will make it more engaging, provided the social context is appropriate. That has actually always been and remains my position, so apologies if this post sounded unilaterally opposed, which it was not meant to be.

But even a well-designed media offering in my medium of choice is not a sufficient criterium for me to actively seek out said offering, sustain interest in and actually *care* about the subject matter conveyed by it.