The study by Mekler and colleagues doesn’t disprove the undermining potential of gamification: It shows that simplistic debates whether gamification “does” or “doesn’t work” are obsolete – as are mere effect studies. From this point on, without proper theories and mediation studies testing them, gamification research won’t learn anything new or important.

The study by Mekler and colleagues doesn’t disprove the undermining potential of gamification: It shows that simplistic debates whether gamification “does” or “doesn’t work” are obsolete – as are mere effect studies. From this point on, without proper theories and mediation studies testing them, gamification research won’t learn anything new or important.

In times where debates about p-hacking and the “replication crisis” reach main-stream media, it is refreshing to see an empirical study that ends flat-out rejecting its own hypothesis. In their Gamification 2013 paper, Elisa Mekler and colleagues set out to empirically test one of the most frequent critiques hurled at gamification: “Do Points, Levels and Leaderboards Harm Intrinsic Motivation?”

A large body of evidence suggests that extrinsic motivation – doing something for outcomes separable from the activity itself, like rewards or social approval – often paradoxically undermines rather than adds to existing intrinsic motivation: doing something because it is inherently enjoyable (Deci, Koestner & Ryan, 1999). The currently most well-supported theory explaining this phenomenon is self-determination theory (SDT, Deci & Ryan, 2000). It argues that people have innate psychological needs for experiences of competence, autonomy, and relatedness. What makes an activity intrinsically motivating is that it satisfies these needs.

A sub-theory of SDT, Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), explains that need satisfaction depends on how people interpret the “functional significance” of external events for their needs (Ryan, 1982): If an event is interpreted as informational about one’s competence, and positive, it supports intrinsic motivation. If an event is perceived as controlling one’s actions from outside, this thwarts autonomy experience and reduces intrinsic motivation. Rewards often thwart intrinsic motivation, CET holds (and studies show) because they are usually perceived as controlling rather than informational. However, rewards can be interpreted as both at the same time, leading to mixed results: Money paid for piece-work can be viewed as both controlling and telling me I’m doing a good job (Deci, Koestner & Ryan, 1999, pp. 653-654). Also, this so-called undermining effect of rewards can logically only occur if there is some intrinsic motivation to begin with.

Are points, levels, leaderboards rewards that undermine intrinsic motivation?

These findings have been popularized in books like Alfie Kohn’s Punished by Rewards (1999) or Dan Pink’s Drive (2009), which in turn led designers and researchers to hypothesise that points, badges, and leaderboards in games and gamified applications might constitute rewards – and therefore thwart intrinsic motivation. Mekler and colleagues set out to test that hypothesis – and found (to their own amazement) no such undermining effect.

They instructed a total of 295 people to tag images online, generating as many useful tags as possible. Participants tagged a total of 15 images each, with every image being shown for five seconds. As for the experimental conditions,

- the “points” group saw a point score, going up 100 points per entered tag,

- the “level” group saw a level display, that is, the point score plus a bar chart with levels, each indicating how many points would be needed to reach it, and an indication of the current level,

- the “leaderboard” group saw a leaderboard – effectively levels, only this time each level was labeled as performance measures of other users,

- and the control group none of the above.

The result:

“Surprisingly, […] not only did points, levels and leaderboards drive users to generate significantly more tags than users in the control group, but no differences concerning intrinsic motivation were found between the experimental conditions.”

Furthermore, compared to the control group, the quality of submitted tags actually increased significantly with game elements, as measured by the percentage of nonsensical tags (like “the”).

Mekler and colleagues don’t disprove the undermining effect: they disabuse us of its common simplifications.

So is gamification absolved from the “undermining effect”? Short answer: no. Mekler and colleagues did not disprove the undermining potential of gamification – let alone the undermining effect. Rather, they thankfully disabused the public debate from some simplistic interpretations of it. Their study did exactly what it said on the box: It asked whether points, levels, or leaderboards as such undermine intrinsic motivation and finds that no, they don’t – not as such. The real conclusion of the study – for me – is that gamification research now needs to up its game and move from such mere effect studies to theory-testing mediation analyses. Let me explain.

What’s in a “Reward”

The first thing to note is that SDT as well as most empirical studies on rewards split out different kinds of rewards, and capture their effect on different proxies or operationalizations of intrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner & Ryan, 1999).

First, undermining effects show less strongly in self-reported interest than in the arguably “harder currency” of free-choice behavior – that is, whether people voluntarily continue engaging in a task after being told that they don’t need to anymore (ibid., p. 646).

Second, verbal rewards – i.e. positive verbal feedback like “good job!” are shown to have a positive effect on both self-reported interest and free choice behavior (though not for children) (ibid., p. 639). This is only the case if verbal feedback is perceived as informational. If it is formulated and perceived as controlling, it thwarts intrinsic motivation (ibid., pp. 652-653).

Third, tangible rewards (like money or prizes) have been shown to have no effect if they are (a) unexpected (you get them after the fact, not knowing that you will) or (b) task-noncontigent – i.e. you get rewarded for just showing up, regardless of how much you engage or how well you perform (ibid., 464). Only expected, task-contingent tangible rewards negatively affect free choice behavior and self-reported interest – but very strongly so (ibid., p. 646).

Finally, these negative effects only occur for interesting tasks, not boring ones (ibid., pp. 650-651).

All these data points are easily explained with CET: Expected tangible rewards and controlling verbal rewards thwart intrinsic motivation because they are typically perceived as controlling (and thus autonomy-thwarting), whereas informational positive verbal rewards are typically perceived as informing about competence and thus motivation-enhancing. Unexpected rewards by definition can’t affect on-task intrinsic motivation as they are only given after the task has ended. And because boring tasks aren’t intrinsicially motivating to begin with, they also show no undermining effect.

How to Read Mekler et al.

Against this background, what does the data of the Mekler et al. (2013) study tell us? First, they studied task performance, not free-choice behaviour. Their behavioral measure therefore doesn’t speak to intrinsic motivation to begin with (which they acknowledge).

Second, SDT scholars emphasise that rewards do have strong effects on motivation and performance – they only caution that certain kinds of rewards come with the side effect of undermining intrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner & Ryan, 1999). Thus, observing increased performance, now matter how explained, is in keeping with SDT.

Third, we have to ask whether points, leaderboards, and levels are rewards, and if so, what kind of rewards. They are arguably not tangible rewards like money – they did not come with payments attached (Mekler et al., 2013, p. 69). They may be classified as a kind of verbal feedback – a quantified, automated form of a person saying “you’re doing a good/bad job!”

Based on the way Mekler and colleagues designed points, levels, and leaderboards, it is plausible that they chiefly afforded being interpreted as expected, positive, and informational: All were continually on display during task. Reaching level 1, 2, 3 (beating 1, 2, 3 people on the leaderboard) required submitting 10 (11), 30 (31), and 60 (61) image tags. At a total of 15 images, reaching at least the first level/beating at least one other player should be arguably easy to attain for healthy, educated human adults: in the control condition, people submitted about 54 tags on average, which translates into easily reaching level 2/position 2 on the leaderboard. Hence, almost no participant will have received the negative feedback of not even besting the first level or competitor.

Also, nowhere did the presentation of points, leaderboards, or levels articulate a controlling “should” or “must” – Mekler and colleagues (2013, p. 69) made sure this wasn’t the case to not confound the effect of such verbal cues with the tested effects of points, levels, and leaderboards themselves. Precisely because of that, these game design elements would have likely been perceived as informational not controlling.

Theory would predict that the tested design elements increase intrinsic motivation. The real counterintuitive finding: they didn’t, and still people performed more

Based on this setup, SDT would predict that these specific point, level, and leaderboard designs constitute positive informational verbal feedback, not tangible rewards nor controlling verbal feedback. If anything, adding them to a task ought not no undermine autonomy, but support competence. Also, as Mekler and colleagues concede, tagging images is not a necessarily inherently interesting activity – so even if the points, levels, leaderboards were perceived as controlling, this wouldn’t undermine intrinsic motivation because there likely was none to begin with. (As they noted in a later comment but not the paper itself, they did pretest the task for interestingness, and found the task slightly above average in “interestingness” – both is accepted standard in SDT-informed studies.)

Hence, an immediately plausible explanation for the increased performance is that the points, levels, and leaderboards indeed worked as positive informational feedback, supporting competence experience, fuelling intrinsic motivation, which in turn fuelled performance. As Mekler and colleagues note, the really interesting finding (from an SDT perspective) is that performance increased, but no increase in competence or intrinsic motivation was found.

They suggest an interaction effect between challenge and feedback as potential explanation: Only if the task at hand is perceived as challenging will the invididual perceive feedback on good performance to speak to its competence – an immediately plausible (though untested) explanation that is in line with e.g. flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) and some (admittedly, mixed) research results on the effects of game difficulty and player skill on gaming enjoyment (see e.g. Jin, 2012; van den Hoogen, 2012; Alexander, Sear & Oikonomou, 2013).

But this only explains the lack of increased intrinsic motivation, not the measured performance increase. Nor do extrinsic rewards explain it, since points, leaderboards, levels were explicitly designed to be detached from any tangible reward or social pressure. (Here, the missing undermining effect in fact supports that people did not perceive the game design elements as extrinsically motivating.) Mekler and colleagues suggest that goal-setting could explain the results – a motivational process different from extrinsic and intrinsic motivation but likewise well-established (e.g. Locke & Latham, 2002; Murayama, Elliot & Friedman, 2012; Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2012). This interpretation is supported by the fact that leaderboards and levels resulted in significantly more image tags than a mere running point score: they offered multiple explicit goals to strive for.

“Just add points” sometimes does work – but why?

But then why did the addition of a mere point score significantly increase performance as well? One explanation would be that people set themselves internal goals. Another would be that the point feedback produced pleasant effectance experiences (Klimmt & Hartmann, 2006) – the pleasure of experiencing that one’s actions change the environment, arguably a “low-level” form of competence that might not be captured by the questions used in the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory Mekler and colleagues used. A third could be curiosity – based on previous experiences with point scores, people expected that something ought to happen when they reach some point threshold: curiosity about that something motivated performance. Other explanations are possible as well, of course.

Mediation FTW! Or: What Now, My Love

In sum, Mekler and colleagues doggedly tested (and disproved) a folk theoretical reading of the undermining effect – that points, levels, leaderboards “as such” undermine intrinsic motivation. A major strength of their study is that informed by SDT/CET, they carefully isolated the effects of points etc. as such from potential attached social pressure or material incentives. A closer look at SDT/CET and existing studies shows that their finding is fully congruent with existing research on the undermining effect. If there is anything to critique, then that said closer look could have suggested to them the opposite hypothesis – namely, that points etc. disconnected from social pressures and tangible rewards should not undermine intrinsic motivation, but serve as intrinsic motivation-enhancing competence feedback. We are left with a puzzling effect (performance increased while intrinsic motivation didn’t) for which we can produce any number of explanations. And this, I hold, is the real result of the study.

Does gamification work/hurt? The answer is mu

Does gamification increase enjoyment and performance? In some instances, yes, that much we know (Hamari, Koivisto & Sarsa, 2014). Does gamification undermine intrinsic motivation? Not necessarily. That much we now know as well. (Though some replications across contexts and with different designs would be nice, of course.) Thus, at this point, the only proper response to the question “does gamification work/hurt?” is mu, that is, un-asking the question because it is ill-formed to begin with.

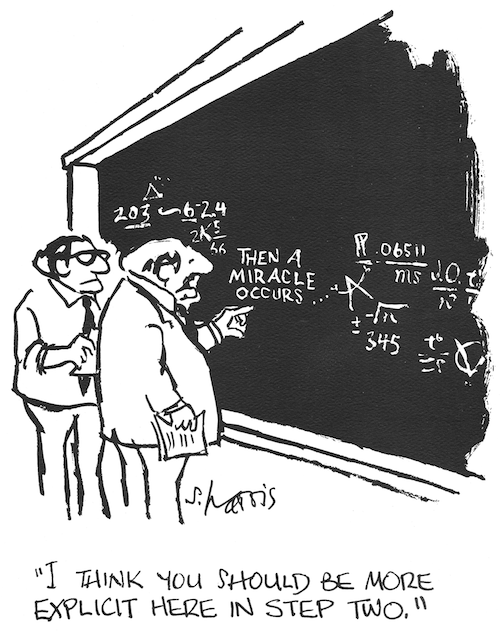

All we know right now is that some design elements commonly labelled “gamification” sometimes do have positive effects on some behavioural and self-report measures. Unfortunately, that is what the overwhelming majority of current industry reports and academic studies test and report, often bundling together multiple design elements at once, each using its own operationalisation for “enjoyment” or “performance” (Hamari, Koivisto & Sarsa, 2014): Does (bundle of design elements X) affect (bundle of self-defined metrics Y)? No matter how many of these studies we have, no matter how big and impressive the reported “increases in engagement”: as long as studies reiterate this pattern, we will only replicate the known finding that “what people call gamification can have positive effects”. What happens between design element bundle X and metric bundle Y, the black box of the human individual, is never and cannot be unpacked by such pure effect studies. Instead, every industry practitioner and researcher fills in “step two” of the equation with their own pet hypothesis of choice.

To make progress in our understanding of gamification, we need to step up our game. Why we see effects, what psychological processes explain how elements affect motivation and behaviour, under what conditions they occur, what specific elements (and element variations and combinations) produce what effects, and again why: that is nothing simple effect studies can tell us. We need to build on theories (like SDT) modelling what mediates between environmental event and behaviour, so that we don’t blindly replicate known findings, identify interesting hypotheses to test, and incorporate new findings into a systematic body of knowledge. We need to start running mediation studies and analyses that operationalise and measure independent, dependent, and mediating variables to see whether the hypothesised mediators do explain how, when, and why element X produces behaviour Y. We need to become more granular and look at isolated design elements, element variations, and element combinations, as well as specific conditions and moderators. We need to agree on operationalisations for the core constructs that interest us – independent design element X, mediating motive Y, dependent behavioural/self-report outcome Z. Otherwise, our studies won’t be able to add up.

To illustrate: How would one run a study testing the undermining effect for gamification? Like Mekler and colleagues, one would isolate specific game elements, and find and pretest a task that is interesting to begin with (though maybe one could find a task that is even more interesting). One would have a self-report measure competence and autonomy experience as mediators (as they did), and measures for intrinsic motivation, ideally self-report (as they did) and free choice behaviour, and if desired, a performance measure. Informed by SDT/CET, one would hypothesise that game elements do undermine motivation if they are perceived as controlling, and thus vary (and pretest) different versions of design elements that should, following theory,

- afford a controlling interpretation: e.g. attaching a monetary payout to measured outcome, and/or using controlling language with regard to them (“you must reach at least X points!”);

- afford an informational interpretation: e.g. directly speaking to the person’s competence (“300 points – good job on a pretty difficult task!”);

- a control group with neither.

Then, run the study and analyse whether controllingly designed elements thwart and informationally designed elements enhance intrinsic motivation, and whether the effect of differently designed elements on intrinsic motivation is mediated by autonomy and competence experience, and whether performance effects are mediated by intrinsic motivation. Such a study would tell us the specific forms and conditions under which specific game design elements have specific effects, and how and why.

In short: There’s work to do. Who’s in?

References

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Oettingen, G. (2012). Goal Pursuit. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 208–231). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does Gamification Work? — A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In HICSS’14 (pp. 3025–3034). Waikoloa, HI: IEEE Computer Society Press.

Klimmt, C., & Hartmann, T. (2006). Effectance, Self-Efficacy, and the Motivation to Play Video Games. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.), Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences (pp. 133–145). Mahwah, NJ; London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kohn, A. (1999). Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717.

Mekler, E. D., Brühlmann, F., Opwis, K., & Tuch, A. N. (2013). Do Points, Levels and Leaderboards Harm Intrinsic Motivation? An Empirical Analysis of Common Gamification Elements. In Gamification 2013 (pp. 66–73). Stratford, ON: ACM Press.

Murayama, K., Elliot, A. J., & Friedman, R. (2012). Achievement Goals. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 191–207). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R. M. (1982). Control and Information in the Intrapersonal Sphere: An Extension of Cognitive Evaluation Theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(3), 450–461.

Pink, D. (2009). Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. New York: Riverhead.

Thanks for taking on this very basic but important topic (measurement models, mediation) which does indeed form a rather large methodological and theoretical gap in the current body of literature on gamification.

As we have noted in the literature review (Hamari et al. 2014) there exists several shortcoming in the current body of research. Your text above highlighted the last one (8).

From the paper:

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does Gamification Work? — A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In HICSS’14 (pp. 3025–3034). Waikoloa, HI: IEEE Computer Society Press. http://gamification-research.org/2013/09/does-gamification-work-a-look-into-research/

“Several shortcomings could be identified during the literature review: 1) the sample sizes were small in some studies (around N=20), 2) proper, validated psychometric measurements were not used (when surveying experiences and attitudes), 3) some experiments lacked control groups and relied solely on user evaluation, 4) controls between implemented motivational affordances were often lacking and multiple affordances were investigated as a whole (i.e.no effects from individual motivational affordances could be established), 5) many presented only descriptive statistics although they could have easily also inferred about the relationship between constructs, 6) experiment timeframes were in most cases very short (novelty might have skewed the test subjects’ experiences in a significant way), and 7) there was a lack of clarity in reporting the results. 8) No single study used multi-level measurement models including all motivational affordances, psychological outcomes, and behavioral outcomes. Further studies should especially try to avoid these pitfalls in order to refine the research on gamification.”

Hey Juho, couldn’t agree more, hence the reference to you ;). I also tried to point at (2) let’s use established operationalisations/metrics, (4) let’s get granular here instead of mushing multiple elements together, (5) let’s test relations. (8) is the best of all worlds. I would add that these methodological shortcomings reinforce and are reinforced by a *theory lack* – subject to a paper currently under review.

Awesome. Thanks Sebastian, for your great explanation of the study. This one is really important to me. And yes….let’s get granular.

IMO, if they wanted to see if their particular design instance of PBL undermines intrinsic motivation, they should consider inviting all the attendees back a few days later and have them do the same tasks again – all without any game elements. If people who used to receive points and standing on a leaderboard performed worse, than they simply became less motivated intrinsically after the extrinsic motivations are removed. If their performance increased, it at least means in a short period of time, the game elements enhanced intrinsic motivation. The same experiment should be done after 2 months to see if any effects stick.

From an application standpoint, the backlash once the extrinsic devices are removed is what is most concerning to experience designers.

Hi Yu-Kai, just measuring performance will never tell you anything about intrinsic motivation, nor about motivation – that’s the (one) point of my post :). If you see a performance increase, it could be a simple skill/learning effect, for instance. To argue that people might get used to game elements – such that their removal reduces subsequent performance – would not be the undermining effect as understood in (and validated for) SDT/CET, but *another* theory to test. (And *why* would getting used to them negatively impact performance if they are removed? Because it confuses people/takes additional time to reorient in a changed interface? Because of “extinction learning”? That would be a completely different paradigm (operant conditioning) that again has nothing to do with intrinsic motivation – behaviourism by definition doesn’t speak about such internal states/processes. And there are many more possible explanations from many more possible theories.) Again, that’s my point: We can’t continue sticking in personal pet hypotheses *why* we see certain effects into mere effect studies: we have to test for the causal paths/psychological processes we hypothesise produce the effects as well.

Hey Sebastian 🙂

I agree with your main premise of the post, and I’m mostly pointing out an improvement on the original study in my mind to get closer to what they are actually trying to find out (which turns out is not necessarily what they claim to find out). You rough group all “PBL” attempts into one bucket and claim that it does or does not have certain side-effects. That’s like saying, “In our experiment, we saw that people prefer human design over nature” when it obviously depends on WHAT is the human design (could just be 1-year old drawing random lines) and WHAT is the nature being compared to (waterfall or just a piece of dirt). Context matters too, as all the examples above can be intriguing if people have seen the others consistently, but not that particular item before.

The problem is that actual motivation is very difficult to test (it’s easy to criticize what other people are doing is wrong, but it’s much harder to design experiments that prove the causal paths/psychological processes that you talk about…unless I’m waiting on some breakthrough research that’s being published by you soon). So far we are only better at measuring behavior and actions than actual motivation (Daniel Kahnman and many other “Blink” related authors all talk about how we have no idea what’s motivating/influencing our own behaviors…such as experiments on walking slower due to old-age associated language in a word game).

On a specific point, it wouldn’t be likely that the new experiment can’t tell from simple skill/learning effects, since there is a control group that should be increasing their skills too. The other possible argument is that because the gamified group did better work than the controlled group the first time through, that additional skill set affects the delta of skills increased/decreased compared to the control group. But even that can be mathematically factored out.

Another big problem is that there’s also still a confusion on defining intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation. Some people still think that non-physical rewards are all extrinsic, and therefore badges are intrinsic (when based on the context, there is a blend of both IMO). Some people think getting a “Thank you” from a friend is extrinsic because the activity may not be desirable but the “reward” makes it worth it. Ultimately, it seems to me that almost all extrinsic motivation connect to intrinsic rewards (even money connects to the “intrinsic” feeling of safety and stability, or freedom). The (if effective) result of operant conditioning IMO is very much an intrinsic motivation boost, trained through extrinsic motivation. Eventually, no external influence or goal is present, but the subject still behaves the same way because of internal forces (either simply from inertia, or mental association with positive/negative feelings).

From my own design standpoint, I generally think of it as – For extrinsic motivation, you need to “incentivize” people to do it; with intrinsic motivation, people would actually pay you to experience it because the experience itself is great (like a theme park, or…..games).

Anyway, if you have more insights/research on how do we actually derive the causal motivation from behavior, would love to learn from it.